Hamlet, shaken by grief and betrayal, famously declared:

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

With the stroke of his quill, Shakespeare illuminates a truth that continues to resonate through philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience: our thoughts and perceptions not only describe our world but also shape it.

I first read Hamlet shortly after separating from the military. I was in my first semester of college, surrounded by students much younger than me. What should have been a refreshing transition quickly turned disorienting.

Political conversations stirred something sharp in me. Naïve twenty-somethings, with no lived experience of war, offered confident opinions about the military. Some equated language with violence, further revealing their misunderstanding.

I was stressed. I was angry. And it was getting in my way.

Like many veterans, I was navigating an adjustment disorder — a dissonance between who I had been and where I now found myself. And that one line from Hamlet lodged itself in my mind. Over time, I came to see just how profoundly that insight applies to all of us, especially when it comes to our mental health.

A Brief Word on Consciousness

To examine perception, we have to start with the most mysterious subject of all: consciousness.

Consciousness is notoriously difficult to define, but at its core, it refers to our subjective experience, the feeling of being aware. It includes our thoughts, perceptions, and the meanings we assign to them.

Consider a red apple. Your brain processes data: shape, hue, context. But you also experience something beyond that, the redness of red. That ineffable sensation is what philosopher David Chalmers calls qualia.

Chalmers distinguishes between the “easy problems” of consciousness, how we process light or detect edges, and the hard problem: why does any of it feel like anything at all? How can physical processes give rise to subjective experience? This explanatory gap — between subjective experience and objective processes — is what makes the hard problem so intractable.

It’s a mystery yet to be solved. But even without fully understanding it, we know that subjective experience, what things feel like, matters. It colors everything.

The Body Keeps the Score

So what does this have to do with mental health?

In The Body Keeps the Score, psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk explores how trauma extends beyond the mind and into the body. Experiences of fear, neglect, or shame become embodied patterns. Muscles tighten. Heartbeat quickens. In some cases, entire systems of the body shift and activate in response to stress.

The body doesn’t just react to what happened; it reacts to how we experience what happened. That distinction is critical.

Trauma researcher Peter Levine calls trauma “not what happens to us, but what we hold inside in the absence of an empathetic witness.” In other words, it’s our internal response, our consciousness, that determines the imprint.

Judgment and Reframing

Centuries before Shakespeare or modern psychiatry, the Stoic philosopher Epictetus wrote:

“It is not events themselves that disturb us, but our judgments about them.”

This ancient insight forms the philosophical backbone of many modern therapies, especially cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). One of CBT’s core tools is cognitive reframing; the act of noticing our automatic thoughts and intentionally shifting the story we tell ourselves.

A rejection may be interpreted as proof of our inadequacy… or as an opportunity for redirection. A bad day may feel like punishment… or a practice in endurance.

We often can't change what happens. But we can change how we interpret it. That shift in meaning and in thinking can make all the difference.

Reflections

As you move through your day, try pausing just a few times to observe your thoughts.

What assumptions are you making about this moment?

Are you telling yourself a story that deepens your suffering?

Where could you apply reframing, even gently?

You don’t need to do this constantly. Just enough to begin noticing the space between event and interpretation — between what happens, and what it means to you.

Seneca reminds us:

“We suffer more often in imagination than in reality.”

And perhaps that is where the healing begins. Not by escaping the world, but by changing the lens through which we view it.

Closing

Looking back, that season of life didn’t change because the world got easier; it changed because I did. I began to notice my thoughts. To challenge them. To reframe.

Now, in my work as a primary care PA at the VA, I see echoes of that process every day. Veterans come in carrying burdens that aren’t always visible on a chart. Old injuries, sure, but also the weight of memories, meanings, and narratives they’ve endured for years.

Many of them aren’t asking for easy answers. They’re asking to be seen. To be understood. And sometimes, to be reminded (gently) that they still have agency over how their story is told.

I don’t always quote Shakespeare in the exam room. But I often return to the same idea:

We may not control what’s happened to us. But we can learn to shape how we respond.

And in that shaping, there’s real healing.

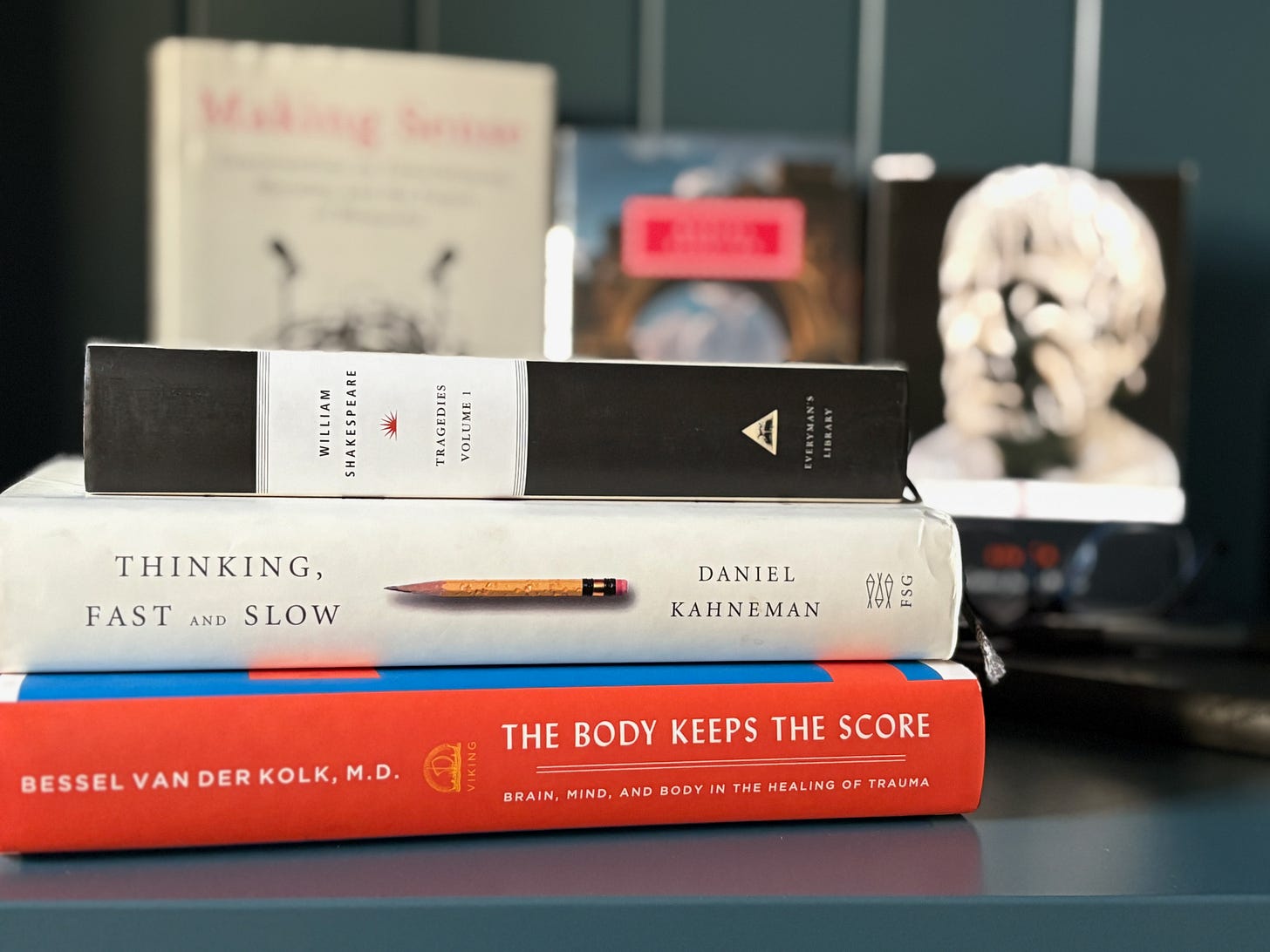

For Further Reading

Bessel van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score

Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow

David Chalmers, The Conscious Mind

Donald J. Robertson, Stoicism and the Art of Happiness

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

William Shakespeare, Hamlet

Disclaimer:

This newsletter is intended for general informational and educational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult your healthcare provider before making any changes to your health regimen.